The case came in sideways, like everything else north of the equator these days.

Over the irradiated murky Atlantic pond, Glasgow didn’t rain so much as accuse. The drizzle slid down the soot-stained tenements like it knew every sin committed inside them. Post-war, post-bomb, post-everything that ever pretended to be civilized. The apocalypse didn’t flatten Scotland the way it did Los Angeles, it hollowed it out instead, left the bones standing and filled the gaps with whisky, guns, and ghosts.

I wore black that night. Not the practical kind.

The statement kind.

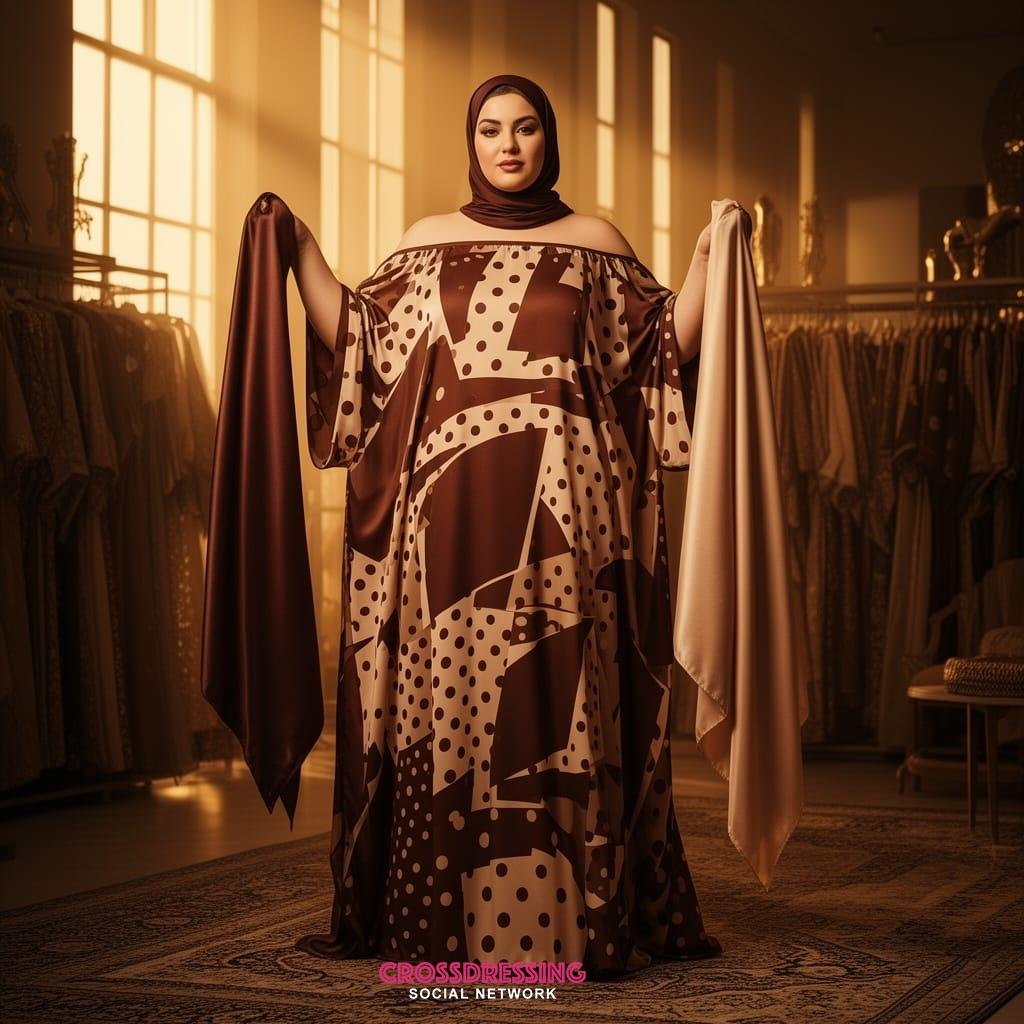

A black oversized tartan satin headscarf wrapped tight around my hair, catching the light like wet ink. Over my face, a sheer black chiffon voile veil, the mourning lace thin enough to breathe through, thick enough to hide regret. The rest of me was Victorian grief dialed up to eleven: glossy black tartan blouse with rococo frills, satin panels hugging me like a second conscience, skirts whispering every time I moved. I looked like a widow who’d buried the world and decided it deserved it.

In Glasgow, that bought me anonymity.

They called me Han here too, though the locals said it like a question. I’d followed the trail across the Atlantic after a shipment of American surplus hardware went missing, Tommy guns, plasma pistols, a few toys left over from the end of the world. Fallout New Vegas tech, Hollywood Hills money, Highland routes. Someone was running iron through the glens and washing it down with single malt older than the war itself.

The back streets off Trongate were crooked enough to make a Dutch cameraman weep. Buildings leaned in close, sharing secrets. Gas lamps flickered like they were afraid of what they might illuminate. I walked slow, heels deliberate, veil fluttering just enough to let the right people notice and the wrong people hesitate.

That’s when the femme fatale found me.

She leaned against a doorway like she’d been waiting for the end of the world to catch up. Hair platinum under a cloche hat, lips dark as a closed casket. Scottish, sharp, and carrying herself like a blade wrapped in silk.

“You’re far from Hollywood, sweetheart,” she said. “And you’re dressed for a funeral that isn’t yours.”

“Everyone’s funeral is mine eventually,” I said. “I just like to dress appropriately.”

She smiled. That was the mistake.

Her name was Moira Blackwood. Whisky broker. Gun runner. Mourner by trade. She dealt in Highland routes, smugglers who knew every fog bank, every forgotten rail spur left behind when the bombs fell south. The Americans supplied the firepower. The Scots supplied the patience.

And someone was skimming.

Bodies were turning up in the lochs. Empty bottles floating beside them like punchlines. Moira wanted to know who was cutting into her business before it turned into a clan war with automatic weapons.

We took a train north that barely remembered being a train. Through valleys drowned in mist and radiation snow. I kept the veil on the whole way. In the Highlands, superstition still worked better than bullets.

The smugglers met us in an abandoned distillery, barrels stacked like tombstones. The tartan of my outfit mirrored theirs, same pattern, different intent. They watched me carefully. Men always did when they couldn’t decide what category to put me in.

That hesitation saved my life.

When the shooting started, I was already moving. Heels skidding on stone, skirts swirling, revolver barking from beneath layers of satin and sorrow. Moira went down fast—winged, not dead. The real culprit bolted for the back door, carrying a ledger thick with names and lies.

I caught him by the loch.

The water reflected us in stark monochrome: him shaking, me looming, veil rippling like smoke. He confessed quickly. They always did when faced with someone who looked like death had chosen tartan satin couture.

I left him there for the deep dark water to judge.

By dawn, the Highlands were quiet again. Moira paid me in whisky older than memory and ammunition stamped with American lies. Fair trade.

Back in Glasgow, I stood in a cracked mirror in a boarding house that smelled of coal and grief. I removed the veil last. Always last.

Another city survived. Another secret buried. Another outfit stained with rain instead of blood.

The world was still tilted. Still broken. Still rolling on at the wrong angle.

But as long as there were shadows to walk and clothes that told the truth my mouth didn’t have to, I’d keep going.

Mourning never goes out of fashion.

Over the irradiated murky Atlantic pond, Glasgow didn’t rain so much as accuse. The drizzle slid down the soot-stained tenements like it knew every sin committed inside them. Post-war, post-bomb, post-everything that ever pretended to be civilized. The apocalypse didn’t flatten Scotland the way it did Los Angeles, it hollowed it out instead, left the bones standing and filled the gaps with whisky, guns, and ghosts.

I wore black that night. Not the practical kind.

The statement kind.

A black oversized tartan satin headscarf wrapped tight around my hair, catching the light like wet ink. Over my face, a sheer black chiffon voile veil, the mourning lace thin enough to breathe through, thick enough to hide regret. The rest of me was Victorian grief dialed up to eleven: glossy black tartan blouse with rococo frills, satin panels hugging me like a second conscience, skirts whispering every time I moved. I looked like a widow who’d buried the world and decided it deserved it.

In Glasgow, that bought me anonymity.

They called me Han here too, though the locals said it like a question. I’d followed the trail across the Atlantic after a shipment of American surplus hardware went missing, Tommy guns, plasma pistols, a few toys left over from the end of the world. Fallout New Vegas tech, Hollywood Hills money, Highland routes. Someone was running iron through the glens and washing it down with single malt older than the war itself.

The back streets off Trongate were crooked enough to make a Dutch cameraman weep. Buildings leaned in close, sharing secrets. Gas lamps flickered like they were afraid of what they might illuminate. I walked slow, heels deliberate, veil fluttering just enough to let the right people notice and the wrong people hesitate.

That’s when the femme fatale found me.

She leaned against a doorway like she’d been waiting for the end of the world to catch up. Hair platinum under a cloche hat, lips dark as a closed casket. Scottish, sharp, and carrying herself like a blade wrapped in silk.

“You’re far from Hollywood, sweetheart,” she said. “And you’re dressed for a funeral that isn’t yours.”

“Everyone’s funeral is mine eventually,” I said. “I just like to dress appropriately.”

She smiled. That was the mistake.

Her name was Moira Blackwood. Whisky broker. Gun runner. Mourner by trade. She dealt in Highland routes, smugglers who knew every fog bank, every forgotten rail spur left behind when the bombs fell south. The Americans supplied the firepower. The Scots supplied the patience.

And someone was skimming.

Bodies were turning up in the lochs. Empty bottles floating beside them like punchlines. Moira wanted to know who was cutting into her business before it turned into a clan war with automatic weapons.

We took a train north that barely remembered being a train. Through valleys drowned in mist and radiation snow. I kept the veil on the whole way. In the Highlands, superstition still worked better than bullets.

The smugglers met us in an abandoned distillery, barrels stacked like tombstones. The tartan of my outfit mirrored theirs, same pattern, different intent. They watched me carefully. Men always did when they couldn’t decide what category to put me in.

That hesitation saved my life.

When the shooting started, I was already moving. Heels skidding on stone, skirts swirling, revolver barking from beneath layers of satin and sorrow. Moira went down fast—winged, not dead. The real culprit bolted for the back door, carrying a ledger thick with names and lies.

I caught him by the loch.

The water reflected us in stark monochrome: him shaking, me looming, veil rippling like smoke. He confessed quickly. They always did when faced with someone who looked like death had chosen tartan satin couture.

I left him there for the deep dark water to judge.

By dawn, the Highlands were quiet again. Moira paid me in whisky older than memory and ammunition stamped with American lies. Fair trade.

Back in Glasgow, I stood in a cracked mirror in a boarding house that smelled of coal and grief. I removed the veil last. Always last.

Another city survived. Another secret buried. Another outfit stained with rain instead of blood.

The world was still tilted. Still broken. Still rolling on at the wrong angle.

But as long as there were shadows to walk and clothes that told the truth my mouth didn’t have to, I’d keep going.

Mourning never goes out of fashion.

The case came in sideways, like everything else north of the equator these days.

Over the irradiated murky Atlantic pond, Glasgow didn’t rain so much as accuse. The drizzle slid down the soot-stained tenements like it knew every sin committed inside them. Post-war, post-bomb, post-everything that ever pretended to be civilized. The apocalypse didn’t flatten Scotland the way it did Los Angeles, it hollowed it out instead, left the bones standing and filled the gaps with whisky, guns, and ghosts.

I wore black that night. Not the practical kind.

The statement kind.

A black oversized tartan satin headscarf wrapped tight around my hair, catching the light like wet ink. Over my face, a sheer black chiffon voile veil, the mourning lace thin enough to breathe through, thick enough to hide regret. The rest of me was Victorian grief dialed up to eleven: glossy black tartan blouse with rococo frills, satin panels hugging me like a second conscience, skirts whispering every time I moved. I looked like a widow who’d buried the world and decided it deserved it.

In Glasgow, that bought me anonymity.

They called me Han here too, though the locals said it like a question. I’d followed the trail across the Atlantic after a shipment of American surplus hardware went missing, Tommy guns, plasma pistols, a few toys left over from the end of the world. Fallout New Vegas tech, Hollywood Hills money, Highland routes. Someone was running iron through the glens and washing it down with single malt older than the war itself.

The back streets off Trongate were crooked enough to make a Dutch cameraman weep. Buildings leaned in close, sharing secrets. Gas lamps flickered like they were afraid of what they might illuminate. I walked slow, heels deliberate, veil fluttering just enough to let the right people notice and the wrong people hesitate.

That’s when the femme fatale found me.

She leaned against a doorway like she’d been waiting for the end of the world to catch up. Hair platinum under a cloche hat, lips dark as a closed casket. Scottish, sharp, and carrying herself like a blade wrapped in silk.

“You’re far from Hollywood, sweetheart,” she said. “And you’re dressed for a funeral that isn’t yours.”

“Everyone’s funeral is mine eventually,” I said. “I just like to dress appropriately.”

She smiled. That was the mistake.

Her name was Moira Blackwood. Whisky broker. Gun runner. Mourner by trade. She dealt in Highland routes, smugglers who knew every fog bank, every forgotten rail spur left behind when the bombs fell south. The Americans supplied the firepower. The Scots supplied the patience.

And someone was skimming.

Bodies were turning up in the lochs. Empty bottles floating beside them like punchlines. Moira wanted to know who was cutting into her business before it turned into a clan war with automatic weapons.

We took a train north that barely remembered being a train. Through valleys drowned in mist and radiation snow. I kept the veil on the whole way. In the Highlands, superstition still worked better than bullets.

The smugglers met us in an abandoned distillery, barrels stacked like tombstones. The tartan of my outfit mirrored theirs, same pattern, different intent. They watched me carefully. Men always did when they couldn’t decide what category to put me in.

That hesitation saved my life.

When the shooting started, I was already moving. Heels skidding on stone, skirts swirling, revolver barking from beneath layers of satin and sorrow. Moira went down fast—winged, not dead. The real culprit bolted for the back door, carrying a ledger thick with names and lies.

I caught him by the loch.

The water reflected us in stark monochrome: him shaking, me looming, veil rippling like smoke. He confessed quickly. They always did when faced with someone who looked like death had chosen tartan satin couture.

I left him there for the deep dark water to judge.

By dawn, the Highlands were quiet again. Moira paid me in whisky older than memory and ammunition stamped with American lies. Fair trade.

Back in Glasgow, I stood in a cracked mirror in a boarding house that smelled of coal and grief. I removed the veil last. Always last.

Another city survived. Another secret buried. Another outfit stained with rain instead of blood.

The world was still tilted. Still broken. Still rolling on at the wrong angle.

But as long as there were shadows to walk and clothes that told the truth my mouth didn’t have to, I’d keep going.

Mourning never goes out of fashion.

0 Commentaires

0 Parts

80 Vue